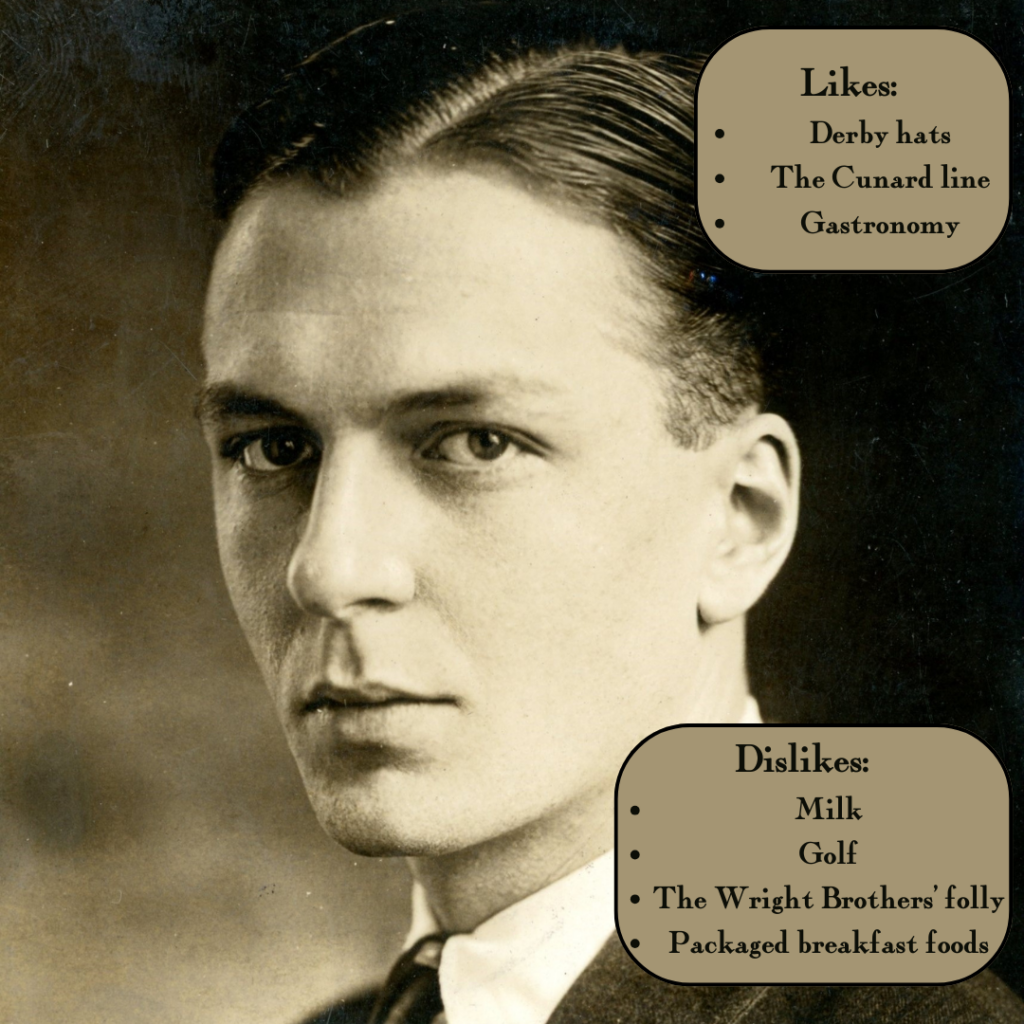

In 1938, the Yale Daily News called Lucius Beebe “a be-spatted and lisle-socked dandy, slick as buttered ice”. Those words were published well over a decade after Beebe’s famous pranks led to his expulsion from Yale (he sealed his fate by disrupting a theatrical performance costumed as a professor of Yale Divinity School, and throwing an empty bottle on stage). The Yale newspaper also extolled the “divine ineluctable flame that once inspired Lucius Beebe to bomb the Morgan yacht with rolls of toilet paper”, while urging undergrads to be more like Beebe after years of “stale” freshman pranks. For better or worse, newcomers to Yale were still being inspired by Beebe’s antics many years after his disgraced departure from the university.

According to my research, multiple contemporary writers used the word “orchidaceous” to describe Beebe– a delightful and underused adjective that evokes qualities similar to those of an orchid. You might be asking yourself “Why did they name a library after this extravagantly floral TP bombardier? Did he do anything else worth mentioning?” Beebe was a polymath who didn’t take days off, well-known as a poet, society columnist, railroad scholar, photographer and publisher, but they didn’t name a library after him. I’m talking about the other Lucius Beebe, the grandson of the one who gave his name to our favorite library.

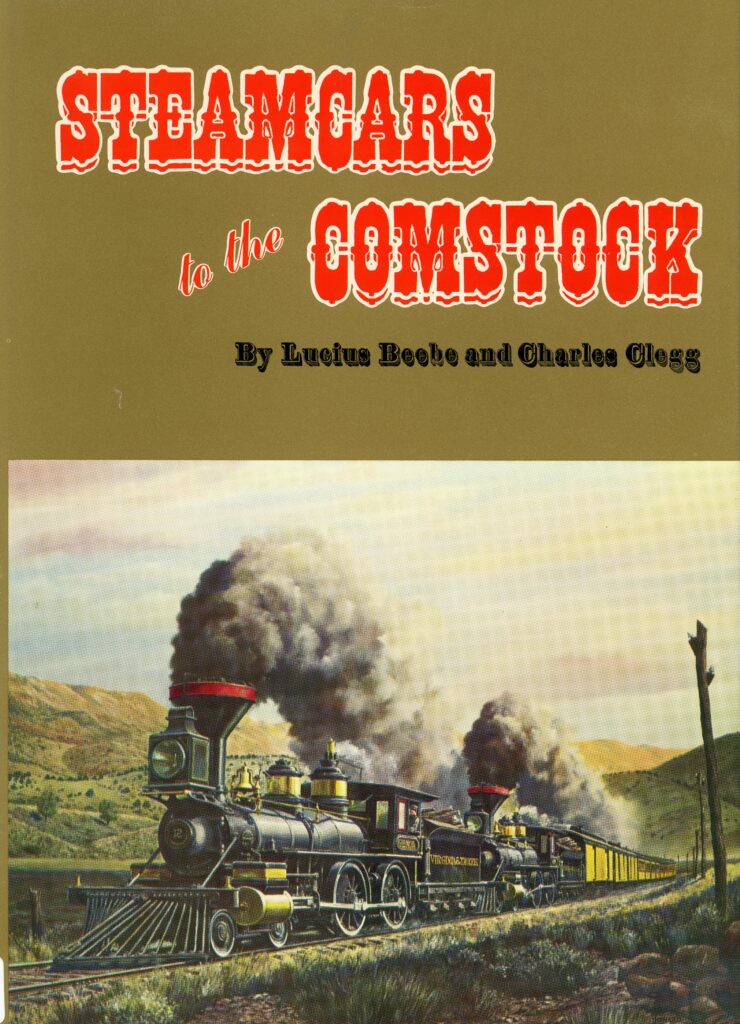

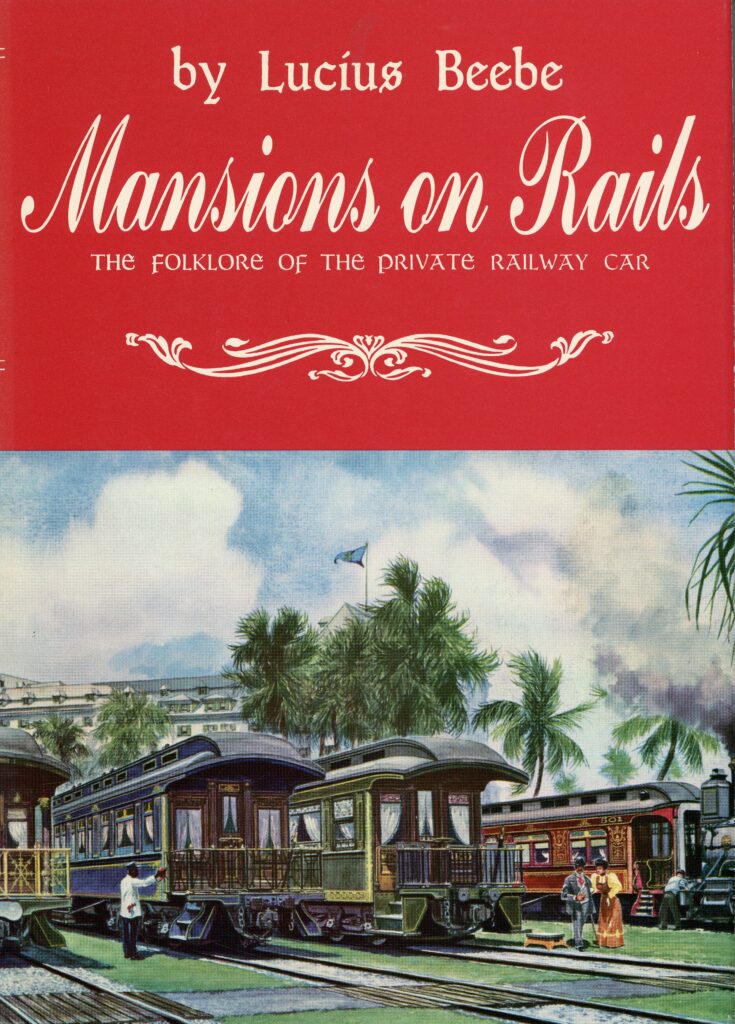

In what has to be one of the most epic meet-cutes of all time, Beebe first encountered his life partner and professional collaborator Charles Clegg at a society brunch in 1941, hosted by socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean, who happened to own the Hope Diamond at the time. Beebe made an unforgettable first impression: an “enormous, almost majestic man with a thunderous voice”, he was casually adorned with his hostess’s notorious 45-carat blue gem and accompanied by three hapless Pinkerton detectives who had been tasked with keeping track of the priceless jewel. He sealed the deal on Clegg’s affection by ending the party drunkenly passed out in a bathtub while clutching the broken pieces of a decorative china pig. It was love at first sight for the two men. They, along with their cherished and pampered dog T-Bone, were thereafter inseparable until Beebe’s death in 1966. Sharing a mutual love of the American railroad, they wrote and published extensively on the subject while traveling the country in their opulently-decorated custom railcars (you can virtually tour one of them here.)

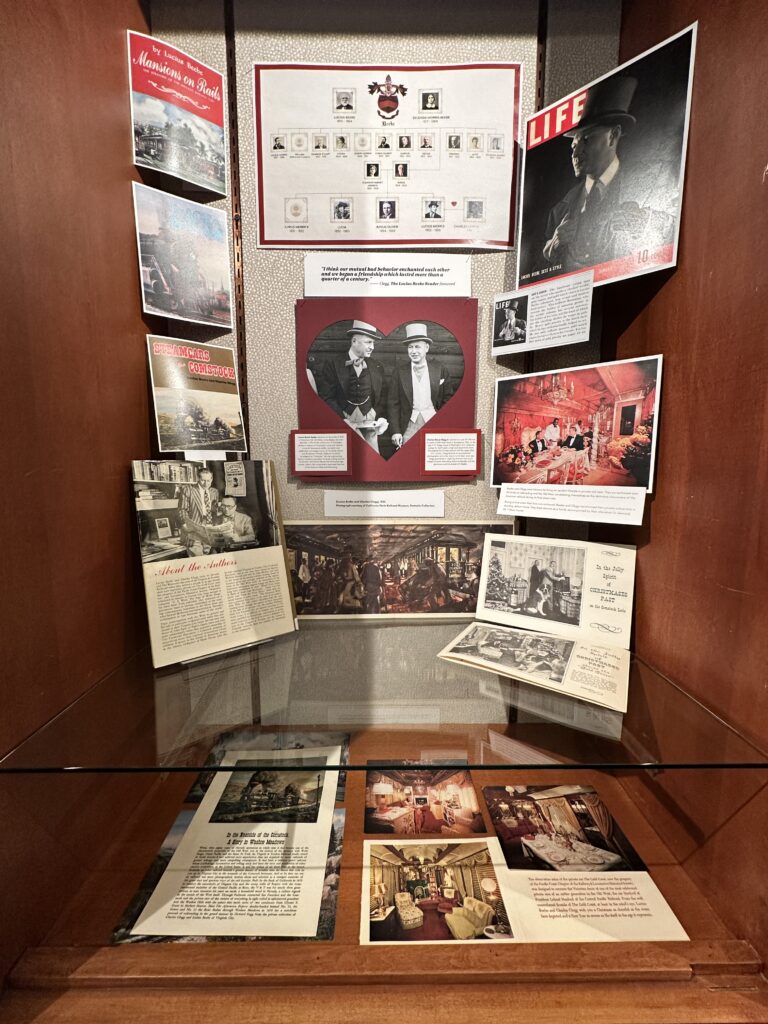

Clegg wrote of Beebe that he “somewhat worshiped” him, and the wistful ache of that phrase, published only a year after Beebe’s death, captures how lonely Clegg was at the loss of such an extraordinary personality – a man who had been at the center of his world. The microhistory of these two men is a glittering, dare I say orchidaceous, tile in the mosaic of Wakefield history, of this library’s history, and of LGBT+ history. You can learn more about their story and see primary sources illustrating their lives together in the display case to the right of the Avon Street entrance, where we’ll be showcasing their unique personalities and cultural contributions until June 2026.